Sailing from a factory shed, round the world, into mystery

Bob Mason was a man with big dreams for his retirement, in 1980 he decided to build his own 18 meter yacht from ferro cement and sail his wife and four children around the world. As the owner of some disused cotton mills in Lancashire, England, Bob had plenty of room in which to construct his leviathan.

He first bought plans for a Hartley 57 from New Zealand, which he then redrew to raise up the poop deck giving the ketch a slight galleon look. With his degree in Engineering from Cambridge University, Bob was well qualified to undertake the monster project and quickly began welding the steel armature which was suspended from the ceiling of the shed in which the yacht was being constructed. The armature then had to be tightly covered with ten layers of chicken wire, five inside, five outside, and the yacht's lines made fair, "this was the hardest part of the entire build," recalls Bob's youngest son, Pete.

Once the armature was completed a team of plasterers spent three weekends applying the cement, one weekend each for the inside, outside and decks, after which the whole craft had to be kept wet with blankets and hoses for a further fortnight.

With the shell completed it was time to put in the Gardner engine Bob had had reconditioned for marine use after it had been rescued from a lorry which was due to be scrapped having traveled one million miles. Water tanks and the under floor storage areas were assembled before the main interior carpentry could begin for the living space. Each of Bob's children designed their own cabins which their father, who is a talented carpenter, then fabricated so that by July 1985 Spinning Jenny of Lune was ready to be towed out of her shed, through the streets of Bolton and launched in the Manchester Ship Canal.

However, even before she touched the water Bob's plans were beginning to unravel. Since he began the project three out of his four children had married, and he and his wife, Mary, had become grandparents. In fact, only Pete, who was still at university studying Naval Architecture, wanted to go sailing at all. With 50 tones of boat to handle it was necessary to address the crewing problem swiftly; chartering her seemed the only option.

After five years of hard work the day of Spinning Jenny's first wetting was extremely nerve wracking. Bob and Pete traveled on top of the yacht lifting up telephone wires over the hull every few yards, conscious that every one that snagged and broke had to be paid for by them. As she was gently lowered into the water it took balls of steel to watch; so many ferro cement boats had failed to float to their marks and so could never be insured, others had sunk straight to the bottom, but Spinning Jenny sat perfectly in the water, her white line being gently lapped by the wavelets. The family started the engine and chugged down to Liverpool where the mast was stepped and Spinning Jenny showed how much she enjoyed a good breeze as she ploughed through the seas on her maiden voyage up to Glasson Dock.

Chartering with up to eight guests aboard, Spinning Jenny went from Wales to the Canary Islands for her first winter, then back to the Mediterranean or up to Scotland and Norway before heading back down to the Canary Islands again when the weather cooled. Many groups of artists chartered the yacht, as did water sports enthusiasts who enjoyed the additional windsurfing and dinghy sailing offered aboard, plus several groups from a religious sect who had dietary and worshipping requirements that were sympathetically catered to by the family.

By 1989 Bob and Mary were ready to come ashore and join their grandchildren on a farm on the island of Anglesey in Wales, so Pete's girlfriend, Steph, joined the boat as cook/mate, while Pete himself became Spinning Jenny's captain. After the couple married they continued to charter until the outbreak of the first Iraq war left Britons unwilling to fly abroad for holidays at just the time when the yacht was on Sardinia's highly expensive Costa Esmeralda. The previous season friends on the Spanish island of Mallorca had assured the couple that if they ever needed work they would be offered it there, so they sailed back to Mallorca and dropped anchor in Porto Colom where Pete began work maintaining other people's yachts while Steph became editor of the local English language daily newspaper. Soon Pete was captaining large yachts for wealthy owners and Spinning Jenny became more of a home than a business; with the arrival of the couple's first son, born on board in September 1993, the transformation into a houseboat was almost complete.

The big green ketch spent the next five years moored in the shadow of Palma de Mallorca's great medieval cathedral, but it was not until the birth of the couple's third child that they finally accepted their sailing days were temporarily at an end and it was time to sell.

In the spring of 1998 a German builder called Eddy Hagdorn bought the yacht with the intention of sailing her round the world, just as Bob Mason had dreamed of doing nearly twenty years earlier. Eddy and his crew remained in Mallorca for six months to familiarize themselves with Spinning Jenny and have Pete nearby to sort out any teething problems, then one bright autumn afternoon they hauled Eddy's beloved motorbike onto the back deck, strapped it down and cast off for Australia where they had booked a berth for the Olympics in Sydney.

Having explored the Great Barrier Reef and braved the Southern Ocean before having a ringside spot at Sydney's fabulous Olympic firework display, Eddy and Spinning Jenny began voyaging north again and by spring 2001 she was in Miami. Pete and Steph were delighted when they checked the yacht's website and found she was due to sail back to Palma in April.

Full of excitement at seeing Spinning Jenny again after her circumnavigation, Pete was thrilled when his mobile phone rang one April morning and he saw Eddy's number come up on the screen. Answering the call, Pete realized that Eddy's phone must have rung his number randomly as the mobile was clearly in Eddy's pocket. Knowing that Spinning Jenny was due home soon, Pete waited a few minutes and then phoned Eddy back to ask if his mobile coverage meant that the yacht was close to land with Eddy aboard. As Pete explained that he was returning the call Eddy's phone had just made to him, Eddy's voice came out harshly, "You are the very last person on earth I would have phoned right now, I've just heard that Spinning Jenny EPIRB has gone off 100 miles out of Miami. She's gone down and I don't know if the crew got off."

Eddy had left the yacht in Miami to return to Germany because a family member was ill, leaving a transfer crew to bring the boat back to Mallorca, but when they were 70 miles off Cape Canaveral a distress call went out.

Thanks to the prompt action and outstanding seamanship of the crew of the 700 foot S/S Mayaguez, the five German crew of Spinning Jenny were rescued moments before she sank into a mile of water. The Mayaguez crew was subsequently honored at the AOTOS Awards in New York City for their skill and quick response during this rescue.

In the decade since the shipwreck Bob and Pete Mason have made several attempts to contact Eddy and try to discover exactly what caused the tragedy, but to no avail. In summer 2010, Steph found references to the rescue on the internet and has been trying to find the names of the transfer crew and contact the crew of the S/S Mayaguez for their versions of the event. Two of the honored Mayaguez crew, Richard Wickenden and Charles Moy, kindly replied giving information about the sea state and the condition of the yacht crew when they picked them up, but neither knew what had caused the accident; was it a failed sea cock? Did she hit a container? What did cause a yacht that had sailed through at least two hurricanes to sink in a force 4 to 5 on a sunny April day? As Bob Mason approaches his 80th birthday this year, he still doesn't know.

The following are inputs from members of the Mayaguez who were on board during the rescue:

Richard Wickenden: As I remember, it was almost flat calm when the boat went down. Her sails were up and luffing in a light wind (Beaufort Force 1). The German crew, piled into a small dinghy, were 150-200 feet off Spinning Jenny. Captain John Morin maneuvered Mayaguez alongside the dinghy, as the Germans had no oars or means of propulsion.

The dinghy, in an overloaded state, had only inches of freeboard. Capt John Morin did a great job maneuvering the big steamship right alongside the dinghy, as the German crew scrambled thru our sideport.

I was on the bridge of our ship and took a last look at the big ketch and she was gone, just an oil slick remained. I went below to have lunch and the German crew were there. They were soaking wet, badly sunburned and badly in need of dry clothes and a good meal. We loaned them our clothes, and they devoured everything they got their hands on in our galley.

It was very sad to watch the boat go down. I am just glad to be of help when it was most needed. This tale turned out well, at least for the crew. On other rescues, in heavy weather, the crews did not fare as well.

Charles Moy: I recently received a note from our (MM&P sec/tres.) and a copy of your request for any information concerning the sinking of The Spinning Jenny of Lune.

The Mayaguez was my last seagoing assignment prior to retiring, following a forty six year career in ships of different companies and various flags.

As you are aware the event took place a number of years ago and having been involved in a number of similar incidents involving rescuing both yachtsmen and refugees, the circumstances didn't immediately spring to mind.

On reflecting, I vaguely remember being called out from my watch below, to assist in the rescue of a number of, what were described as five or six German nationals, clinging to a sinking yacht.

On reporting to the bridge I could see the endangered vessel sitting quite low in the water, possibly on her side and as there was a fair sea running (perhaps force four or five?) realized we had arrived none too soon and appeared it would require a bit of luck on all our parts. I recall we approached as close as possible attempting to make a lee for them, keeping them on our port hand.

Prior to my leaving the bridge, on seeing they had an inflatable dinghy tied alongside, it was decided it would be better if all hands could get into the dinghy then we would approach as close as possible and when given the word I would open the port side side-port, bringing the men on board as quickly as possible.

We had rigged a boat rope and cargo nets over the port side, with the usual heaving lines and life rings. Our objective was as I mentioned, to have the yacht's crew abandon ship by getting into the dinghy and we would quickly approach and open the port side side-port where we had further cargo nets and a pilot ladder ready.

Fortunately we were fairly light and had six or more feet of freeboard from the sideport. We were lucky and things went according to plan, I was at the side-port with a couple of sailors and on receiving the word via radio, opened the side-port to see the dinghy approaching down our port side.

Again we were lucky, we threw them lines which they used to both pull the dinghy and secure it under the side-port, there was a bit of bobbing and falling back in the sea plus a few skinned knuckles and bruised knees, but everyone eventually got safely on board. And we were fortunate not to take any seas through the side-port.

As for The Spinning Jenny my sighting was brief and one couldn't tell what kind of craft she was, either she was on her side or possibly dismasted, perhaps you may find out from one of the other mates or Capt. Morin as my last sighting was brief, immediately having to cut adrift the dinghy, close the side-port and deal with the rescued crew members. Plus we had a schedule to keep and were quickly on our way to our next port.

Strangely enough, I don't recall ever inquiring as to what went wrong, suppose I didn't want to embarrass anyone at the time.

Best regards,

Charles Moy.

Building armature: making the iron frame of the ferro cement boat and then weaving 10 layers of chicken wire onto it.

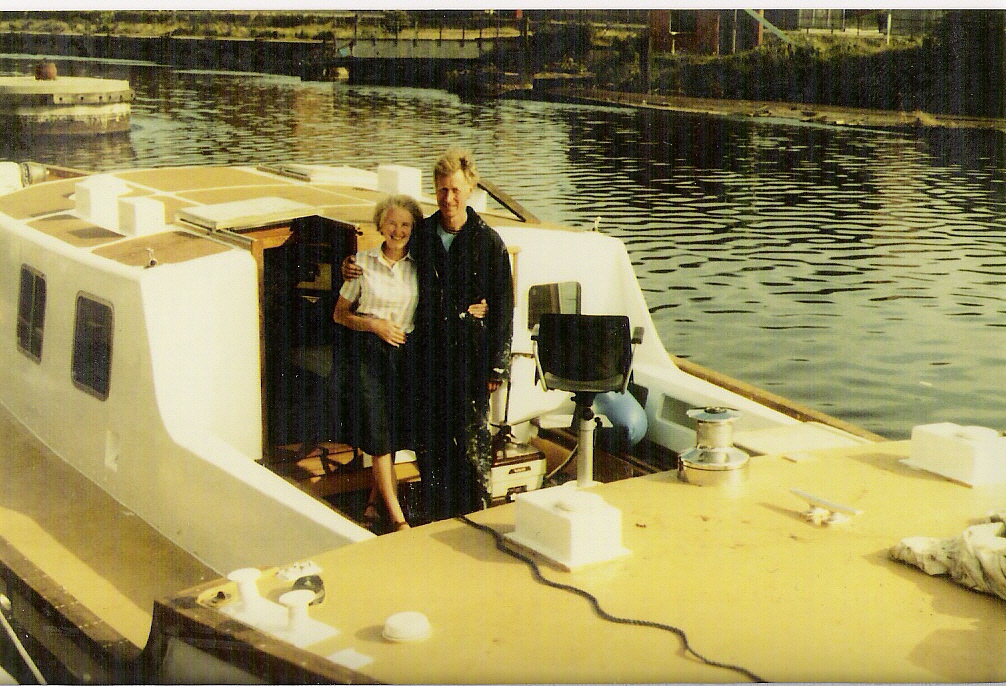

Bob Mason and his wife, Mary, half an hour after launching. After five years of work she floated perfectly to her marks.