The Great Exchange

The global exchange of cultures, plants, animals, and, disease.

Reprinted with permission from Mariners Museum, Newport News, VA www.mariner.org

It was called the Age of Exploration. It was the era during which explorers threw open the doors to new lands and not only made exciting discoveries, but also helped develop a larger global economy. The people living on the continents of Africa, Asia, and Europe, known as the Old World, already had access to each other, but broadened their world when they introduced themselves to the Americas, bringing with them their cultures, plants, animals, and, unfortunately, disease. In turn, the New World sent its cultures, plants, animals, and disease back to the Old World.

This was the Great Exchange.

Early explorers such as Christopher Columbus set sail for Asia, hoping to bring back exotic spices, gold, and other goods to be sold at reasonable prices. Spices were valued because Europeans used them as flavoring for food, preservatives, and medicine.

In fact, spices such as pepper and cloves made the long journey from Southeast Asia (modern day Indonesia) to India, then Arabia, and finally to Italy. As the journey progressed, as one trader followed the other, each increased the price of the spices as they moved westward until the price was so high in Europe, only royalty could afford to buy them. The goal of the early explorers was to cut out the middlemen in India, Arabia, and some places in Italy. By having a more direct route, spices wouldn’t be priced so high and more people could afford them.

When Christopher Columbus finally landed in America, he did not find the Asian pepper, cloves, and other spices he was looking for, but, instead, found new and exciting products, encountered new cultures, and saw strange and wonderful animals. In fact, Europeans thought this was a terrific opportunity to expand their borders, produce valuable commodities, develop new settlements for their crowded countries, and spread Christianity to the Native people in the Americas. The Spanish, Portuguese, French, and English all began to mine silver and gold, grow tobacco and sugar, and send thousands of people to build settlements in their territories. That was all well and good, but the new settlers in America also wanted the familiar foods and animals from their homeland. When they brought these plants and animals from their homes to the New World, these new things changed the landscape, affected indigenous animals, and exposed Native American populations to new diseases.

Plants

Wheat, Rye, Oats: (Old World)

The European settlers loved their wheat bread. Although wheat was less productive per acre than any other grain, they had to have it. Growing wheat, rye, and oats was unsuccessful in the tropical, sea-level colonies of the Americas, but these grains became widely planted in dry, temperate climates, and in the higher altitudes of places like Mexico in Central America and Peru in South America. By the mid-1500s both regions were producing enough to supply remote areas of the Spanish colonies. Native Americans in the lowland regions remained faithful to their longtime staple, corn, and were slow to adapt to these new grains. Oats were more popular with Northern Europeans and were adopted into the cooler climates of northern Americas. The introduction of the hybrid red oat has allowed for winter cultivation in southern climates. Closely related to wheat, rye was used to make brown breads. All their efforts worked—today, wheat is eaten around the world from China to Arabia, Europe to America.

Coffee: (Old World)

The North Africans and Arabians first discovered the rich brew that came from the coffee bean. It was not introduced to Europe until the 17th century because Arabian sultans closely guarded the plants and controlled production. The Turks finally introduced coffee to the Mediterranean through trade with Venice and in 1650, the first coffee shops appeared along the canals of the Italian city. In 1683, coffee was first sweetened with sugar.

By 1700, the coffee plants themselves had found their way to greenhouses in Europe. One of these plants traveled even further to the French colony of Martinique in the care of a military officer. It flourished in the abundant rainfall and warm temperatures and soon spread throughout the Caribbean and South America. The Portuguese then introduced coffee to their colony in Brazil and the South American coffee empires were born.

Lemons/Oranges: (Old World)

These popular evergreen citrus trees have been around for a very long time and are probably native to India or Southern China. Lemons have been cultivated in the Mediterranean region since about 200 CE. Sour oranges have been cultivated since 1300, with sweet oranges following one hundred years later. In 1493, Christopher Columbus brought lemon seeds to Haiti and by 1565, the Spanish and Portuguese had introduced oranges to Florida and the West Indies. In the 16th century, a traveler named Jose de Acosta wrote about the orange groves he had ridden through. He asked, "Who has planted the orange groves?" He was told, that "oranges being fallen to the ground, and rotten, their seeds did spring, and of those which the water carried away into diverse parts, these woods grew so thicke."

Millet and Yams: (Old World)

Millet, a drought-resistant African grain, was probably domesticated around 3000 BCE. Yams were cultivated in sub-Saharan Africa as early as 5000 BCE. (Imagine!) and by 1500 they had become the principle crop in much of the continent. They also became a food readily available for distribution to slaves during the Middle Passage to America. Europeans living in America encouraged their African slaves to grow yams and millet to help them adjust to the New World. Today, these two Old World foods are still around. Many cultures still include millet in their diet and it is also used in American birdseed. Yams are still eaten, although they’re confused with sweet potatoes, which is a New World product. Surprisingly, yams and sweet potatoes are totally different vegetables. Yams can be identified by their white flesh and woody skin. Yams also taste sweeter than sweet potatoes.

Cotton: (Old World)

Imagine how long cotton has been around. Historians have found evidence of cotton in the Indus Valley of India (Pakistan today) dating back to 3000 BCE. It is also recorded that Chinese emperors wore cotton robes more than 1,300 years ago. Spreading west to Egypt, cotton has been found in pyramids, eventually made its way to Europe, and then to the Americas. Some sources state that cotton could have been in the Americas before European arrival, but it was first fully cultivated in America by the Spanish when, in 1556, a crop was grown and harvested in what is modern-day Florida. America, with its warm and temperate climate, became a prime location for growing cotton. While the cotton grown in Egypt had short fibers, making it difficult to spin into thread, the American variety of cotton had a longer and wetter growing season causing it to produce a longer fiber. This made the cotton softer and easier to spin. Cotton is a labor-intensive crop and African, then African-American slaves were used to grow and harvest the crop. Cotton is still grown today in North and Central America.

Cotton Plant, Asia, the First Part: Being an Accurate Description of Persia, and the Several Provinces Thereof, 1673, From The Library at The Mariners’ Museum.

Sugar: (Old World)

Man has been craving sweets for centuries. Sugar cane, a major source of sweet-tasting sucrose, has been cultivated in New Guinea for ten to twelve thousand years. From 350 BCE to 350 CE. it was adapted to North Africa and Europe. Sugar cane was brought to the New World by Christopher Columbus during his second voyage in 1493 and was cultivated in Santo Domingo. In 1516, sugar was first shipped to Spain from the Americas. As consumption of sugar in Northern Europe rose from the 17th century onward, demand for sugar and the planting of it in the New World eventually developed into quite a profitable business. Why?

Sugar production, though agricultural, is highly industrial as well. This created the need for a labor force and slaves became that force. Some of the first Africans brought to the Americas as slaves came with the Portuguese for the sugar plantations. The “triangle trade,” slaves to the Caribbean, sugar and molasses to North America, and rum to Africa, was long an economic staple of the English colonies.

For more information on the transatlantic slave trade: http://www.mariner.org/captivepassage/index.html

Indigo: (Old World)

This plant, which produces a clear, bright blue dye, has been popular for 4,000 years. Britons, who called it woad, painted their bodies with it. Still popular much later, the blue of Levi Strauss’ jeans came from the indigo plant. It was imported to the New World, where it became a traditional subtropical/tropical plantation crop. Why? Producing indigo dye is labor-intensive, so it became a crop closely tied to slavery. Since the advent of synthetic dyes though, the demand for this crop has almost disappeared.

For more information on the transatlantic slave trade: http://www.mariner.org/captivepassage/index.html

Tea: (Old World)

Tea is truly a worldly drink. In 1000 BCE, tea was introduced to China from Tibet, were the plant grows wild. The Chinese discovered how to steep the leaves with boiling water and introduced the drink to Dutch and Portuguese explorers. A Venetian, Giovanni Ramusio, drank the first recorded Asian tea that was imported by Russian merchants in 1559. The Dutch started growing tea in Java, India, and Sri Lanka, and in1657, tea arrived in England from Holland and the Dutch East India Company. We know how fond the English are of their tea. (Could crumpets be far behind?) Tea was then exported to the American colonies through companies that set the prices. With the additional taxes of the British government, tea became too expensive to drink. It was not until the age of clipper ships, which could sail quickly to China and India, and Queen Victoria of England, who made taking “high tea” in the afternoon popular, that the price of drinking tea became more affordable. In 1904, it is thought iced tea was accidentally discovered at the St. Louis Exposition.

Rice: (Old World & New World)

By 4000 BCE, rice had become the staple crop of Asia. Native Americans also harvested a coarser wild rice that grew in marshes. Asian rice was softer and easier to chew than wild rice and it became the rice of choice for most of the world. It was quickly adopted by Americans to plant in the low, wet, tropical areas of the New World, places where the American staple, maize, would not grow. Cultivating rice was labor intensive and Africans that grew rice on the West Coast of Africa were brought to America as slaves. They helped develop the crop in the southern United States. Today the United States exports a large variety and quantity of rice.By 4000 BCE, rice had become the staple crop of Asia. Native Americans also harvested a coarser wild rice that grew in marshes. Asian rice was softer and easier to chew than wild rice and it became the rice of choice for most of the world. It was quickly adopted by Americans to plant in the low, wet, tropical areas of the New World, places where the American staple, maize, would not grow. Cultivating rice was labor intensive and Africans that grew rice on the West Coast of Africa were brought to America as slaves. They helped develop the crop in the southern United States. Today the United States exports a large variety and quantity of rice.

For more information on the transatlantic slave trade: http://www.mariner.org/captivepassage/index.html

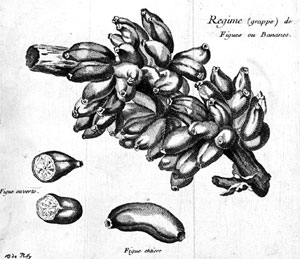

Bananas: (Old World)

Bananas, a native of Southeast Asia, are well suited to wet, tropical areas. They adapted well to the Caribbean and South American lowlands when they were introduced from the Canary Islands. They quickly became a staple crop of tropical America. Today the majority of bananas consumed in the United States and Europe are from the Americas.

Bananas, The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West, 1794, From The Library at The Mariners’ Museum.

Peanuts: (New World)

Peanuts, a native crop of South America, have been cultivated for over 2,000 years. The Spanish took them from South America back to Spain, and then Spanish traders introduced peanuts to West Africa. The plant was widely grown there and returned to America aboard slave ships. Do you know where the nickname for peanuts, “goober,” came from? It came from the Congo people’s name for them, “nguba.” Peanuts became an essential agricultural element in the sandy coastal soils of China where it played an important role in crop rotation when coupled with rice. In the 17th century, peanuts were introduced to the Virginia colony, but were considered a poor man’s food until the 1900s. In fact, Union soldiers took peanuts home after the Civil War, and they became snacks for the working class. In 1903, scientist George Washington Carver developed 300 uses for peanuts, including peanut butter. It might surprise you to know people in the United States did not eat very many peanuts until after World War II.

Beans: (Old World & New World)

Traditional dried beans were under cultivation in 2000 BCE and have long been a staple of the Americas. The ancient Indian practice of planting corn, beans, and squash together was a simple but very effective cultivation technique. How does it work? Corn grows straight, beans grow around the stalk of corn, and squash covers the ground, preventing weed growth. Beans also have another advantage: fixing nitrogen into the soil. This essential process hastened their adoption by European, African, and Asian farmers who recognized the benefits of a food source that improved the soil. Often called "poor man’s meat," American beans are particularly high in protein.

Aztecs making chocolate for a principal god, Vitzilipuztli, The General History of the Vast Continent and Islands of America, Commonly call’d West-Indies, 1725-26, From The Library at The Mariners’ Museum.

Cocoa: (New World)

Did you know chocolate comes from trees? Well, sort of. The fruit of the Cacao, a tropical South American tree, produces cocoa beans from which chocolate is made. It’s a valuable crop. Cocoa was cultivated for more than a thousand years in Mexico, and Christopher Columbus first encountered natives trading cocoa beans as money. It was not until Hernan Cortez met the Aztecs that the Spanish were introduced to chocolate. Aztecs mixed corn, ground cocoa beans, vanilla, chilies, and achiote (or annatto) seeds in hot water and stirred quickly, making a frothy drink. Achiote gives chocolate a reddish color. One of the early explorers wrote the following about Aztec chocolate making:

"The Spaniards, to make chocolate, mix maize (by the mexicans call’d Tlaolli) either whole or ground, or boyl’d before with chalk, moreover, they put the red kernels also in the drink, which grow in the fruit of the Achiote-tree. Of the kernels, which are dry and cooling, boyl’d in water, and stirred till it comes to a pap, and takes away all rastes (???) that cause vomiting." From America: Being the latest, and Most Accurate Description of the New World; Containing The Original of the Inhabitants, and the Remarkable Voyages Thither, by John Ogilby 1671. Cortez sent cocoa beans to Spain, and the Spanish added sugar to the drink. They also kept it a secret until 1606 when the Italians started drinking chocolate. Chocolate became a popular drink throughout Europe and the European colonies. In 1840, our enjoyment of chocolate resulted in the development of the chocolate bar. Today the majority of Cacao is grown in tropical Africa where it has become a major export crop. According to economists there will be a worldwide shortage of cocoa in the next ten years as the demand far exceeds supply.

Potato: (New World)

Native to the Andes Mountains of Peru, this South American staple was introduced to Europe in the 16th century where it was not well received. On the other hand, potatoes were introduced to North America in the 18th century, and they flourished in the northern latitudes. It was also the perfect crop for the cooler climates of Northern Europe, and by the 19th century the potato had become a staple of Germany, Russia, and Ireland. Potato cultivation enabled larger quantities of food to be produced per acre, playing a part in creating a population boom. In Ireland, it is estimated that the poorer classes ate up to 19 potatoes a day per person with little else in their diet. How would you like to only eat 19 potatoes every day? From 1845 to 1850, this reliance on the potato became a major problem when a fungus or blight attacked the potato crop. As potato plants died, there was widespread starvation, leading to the deaths of at least one million people in Europe. This also led to a major migration of famine-struck peoples to other countries, including the United States. Today, potatoes are still popular and it is estimated that every American eats 120 pounds of potatoes a year.

Maize: (New World)

Corn—or maize—was the principle grain crop of the Americas. Originally cultivated in Mexico, by 3500 B.C. it had spread throughout the Americas. Christopher Columbus, acknowledging its importance in the New World, introduced it to Europe. Like potatoes, maize’s tremendous production enabled more grain to be grown per acre allowing populations to increase. To keep that production healthy, maize needed regular rainfall for ideal growth. In the semi-arid climates of the Mediterranean and Middle East, where rainy seasons were followed by drought, corn did not fare well and therefore it had little effect on their cultures. The cultivation of corn in Africa began soon after the exploration of the Americas. Regular rainfall there proved it to be a reliable crop and it was quickly adopted. By 1561, corn was being grown in East Africa; China, following suit, began cultivation in the 1550s.

Pineapple: (New World)

Probably first cultivated in the highlands of South America, pineapples were introduced to Europe by Christopher Columbus. In the English colonies of Virginia, Maryland, Georgia, and the Carolinas, pineapples were considered the symbol of hospitality because they were so difficult to produce (taking up to two years to grow), then ship north, and arrive fresh in North America. A truly wealthy host offered pineapple to his guests. Pineapple is cultivated today in the tropical and semi-tropical highlands of Brazil, China, and Mexico, but it is Hawaii that produces one-third of the world’s supply of pineapple.

Chili Peppers: (New World)

Christopher Columbus took native chilies, including hot and sweet peppers, back to Spain. A crewman wrote, “In those islands there are also bushes like rose bushes, which make fruit as long as cinnamon, full of small grains as biting as (Asian) pepper; those Caribs and the Indians eat that fruit like we eat apples.” By 1569, over 20 varieties of pepper had been adapted to the Spanish climate. Today, chilies are found in all cultures of the world. Paprika, a Hungarian staple, is an example of this adaptation.

Cassava/Manioc: (New World)

The root called cassava in the West Indies and manioc in Brazil is native to the tropical Americas. Cassava is an important food in areas where corn and potatoes will not grow. This large plant has shoots and young leaves that are edible, but its root is the staple product. It’s so important because it grows in areas with soil too poor to support other crops. How is it used? The roots are cooked and dried then crushed into a powder. Have you ever eaten tapioca pudding? Cassava is used to make tapioca, farina and cassava bread. The starch of the root is referred to as arrowroot, another useful ingredient in cooking. The plant was exported to places like Africa where it has become an important food source.

Tobacco: (New World)

Christopher Columbus wrote that the natives of San Salvador “drank smoke.” What an intriguing description and what a way for the Europeans to learn about tobacco. It was smoked through a small pipe called a “tobago,” and it became known as “tobacco.” Originally consumed for its medicinal qualities, tobacco soon spread throughout the Americas. The Spanish began to grow tobacco in their American colonies and export it to the rest of Europe. Europeans quickly became addicted to tobacco. Spain controlled the monopoly on tobacco until John Rolfe, of the Virginia Colony, sent a shipment of tobacco back to England in 1619. From that point on, English colonies such as Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina grew tobacco and supplied Europe. Tobacco was a labor-intensive crop and its production became a driving force in the importation of slaves to the North American colonies.

Tomato: (New World)

Native to the Andes of South America, this bright red fruit (That’s right, it’s a fruit, not a vegetable!) was originally shunned by Europeans who thought it to be poisonous. Eventually, tomatoes became accepted and American colonists began growing them, even consuming more tomatoes than their European cousins. Today, they are grown worldwide and are an essential source of vitamin A and C. Imagine Italian cooking before the tomato! Italians did not add the tomato to their cooking until the 1860s.

Allspice: (New World)

Allspice was the one true spice that Christopher Columbus brought back from the New World. A fruit that resembles a peppercorn, allspice was discovered in the West Indies growing on the island known today as Jamaica. Attempts were made to grow allspice in other parts of the world, but they were not successful. Allspice combines the fragrance and flavor of cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg. Today, it is still primarily grown in Jamaica.

Cinnamon: (Old World)

Do you know where the cinnamon stick in your hot apple cider comes from? Cinnamon is harvested from a tree native to Sri Lanka and India that grows near the ocean. The tree has a double bark and the inner section is “cinnamon.” That inner bark is dried in the sun until it has rolled up and become a light brown color. This was one of the very first spices early European explorers attempted to find in the 15th century. The Portuguese, then the Dutch in 1636, controlled Sri Lanka and cultivated the cinnamon groves there. They also controlled the price. When the English East India Company took control of Sri Lanka in 1796, they set the price for cinnamon. Today, Sri Lanka is the principal cinnamon-producing country in the world, but it is also grown in Java, India, and the Seychelles.

Cloves: (Old World)

Cloves, the flower buds from clove trees, are a spice grown on the Isle of Amboina in the Moluccas Islands. The buds are dried to a dark brown hue to prevent them from decaying. The word “clove” comes from the French word “clou” meaning nail; cloves are so named because of their resemblance to small nails. Cloves were first recorded in ancient China where members of the court could not speak to the emperor without a clove in his or her mouth. Why? It freshened the breath. Cloves were used as medicine for toothaches or upset stomachs as well. Today, cloves are also grown in Zanzibar and in Madagascar.

Ginger: (Old World & New World)

Ginger is indigenous to India and China, and has been cultivated in Asia for 3,000 years. It’s made its way, though, to many places, helped, in part, because the root is easy to transport and to cultivate. The Arabs introduced it to East Africa, the Portuguese to West Africa, and the Spanish and Portuguese to the West Indies and Central America. Ginger is marketed in two forms: preserved green or dried and cured. There are also two varieties of ginger: black ginger with skin, and white ginger without skin. Wild ginger was found growing in America and the natives used it to flavor hominy grits. Ginger was also used as a “warming” medicine to warm upset stomachs.

Nutmeg/Mace: (Old World)

This valuable crop, with 80 species of nutmeg trees and bushes, blooms and bears fruit year round. The fruit is picked when it is fully ripe and the outer husk is removed. The inner husk, which is red in color, is dried separately to make a spice called mace. The seed inside is also dried to create nutmeg. Nutmeg was used in ancient China and traveled on caravans to Europe. In the 1620s, the Dutch controlled the cultivation and production of nutmeg. How? They soaked the nutmeg in lye to kill the germ and prevent anyone else from growing a nutmeg tree. Today, it is grown in the Suriname, West Indies, the Island of Penang, and the Banda Islands.

Pepper: (Old World)

Pepper, above all other spices, was the most valuable to Europeans. In fact, an ounce of pepper could be traded for an ounce of gold. Pepper was popular even in Roman times, and it was traded in the Roman Empire. When Rome fell to the Goths in 408 A.D., as a tribute, the Goth King demanded gold, silver, and 3,000 pounds of pepper. Of course, Europeans used pepper as it was intended, to flavor their food, but also, in an age before refrigeration, to help preserve their meat. Vasco da Gama’s main goal in finding an easier sea route to the east was to bring back pepper.

What is pepper, exactly? It’s the fruit of a shrub that grew wild in the Malabar district on the West Coast of India. Today, 80% of the world’s pepper is grown in the Netherlands’ Indies. Most of it is now cultivated on plantations where shrubs are grown from seeds or cuttings. Drying unripe berries until they are black makes black pepper. Grinding only the seeds taken from the berry makes white pepper.

Vanilla: (New World)

Think of the fragrance of vanilla. It only seems fitting that it comes from a beautiful flower, doesn’t it? Vanilla, the seedpod of an orchid, is a spice originating in the tropical rainforests of Central America. Because of the popularity and profits associated with vanilla, Mexico developed a monopoly on growing the beans until 1841. It is now produced as well in Madagascar, the Comoro Islands, and Reunim where the French and the Dutch introduced it.

Tahiti and Hawaii are also becoming major vanilla producers. Surprisingly, the vanilla bean has no flavor until the beans are warmed and put into a “sweatbox” to ferment. Because valuable beans have been stolen off the vine, they are branded using a cork with sharp pins. But even with these efforts, there is not enough real vanilla to fill the need for the popular flavoring in the United States alone. That’s why most vanilla-flavored products we eat are made from synthetic vanilla developed in 1874.

Animals

Horses: (Old World)

The horse is the one animal from Europe that Native Americans in both North and South America embraced wholeheartedly. Native Americans were first afraid of the large animal, but soon discovered it was quite useful in their environment. In fact, the horse became very important in many cultures, changing the way people hunted for food and fought wars, increasing their value in society, and influencing who and how they married.

Horses lived in the Americas way back during the Pleistocene period, but they eventually died out. When the Spanish re-introduced them in 1492, horses had difficulty adapting to the warmer temperatures. But, as the Spanish explorers began to breed the horses in America, the animals became better adapted to the new climates, even flourishing in more northern areas. By the 1580s horses had multiplied, becoming so numerous it was difficult to count them. Not everyone was enthralled with the horse, though; on the Pampas, in South America, Native Americans there resisted adopting the horse until the 19th century.

Horses in North America continued to increase due to constant Spanish breeding and importation. By 1690, large herds of wild horses were roaming in areas known today as Mexico and Texas. In the 17th century, the French, English, and Dutch brought in their own horses, which became the basis for many modern American horse breeds.

As horses thrived, so did vaqueros, gauchos, and cowboys. They used the horse as the main tool used to round up wild herds of buffalo or even cattle. The horse also allowed native groups of the North American plains to hunt buffalo more efficiently. Eventually, by the 19th century, the buffalo was almost wiped out when Native and white settlers used horses to over-hunt the vast herds.

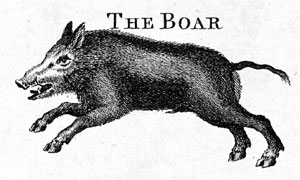

Pigs: The Perfect Colonists (Old World)

Pigs were first brought to Espanola and the Antilles in 1493, when Christopher Columbus made his second voyage. They were the perfect colonists. Why? They weren’t picky and did not need to be fed a special diet. They could eat vegetables of any kind including cassava, as well as shellfish, and even small animals. With a healthy diet, and no natural predators, pigs reproduced quickly in the dense forests. And while pigs quickly adapted to their new environment, the environment did not quickly adapt to pigs; they had a dramatic impact on the native ecosystems, rooting in the forests, killing vegetation, and causing erosion. Pigs adapted well to North America in the English and French colonies, but it was the Antilles that were hit the hardest with wild pig populations.

If you look at a map of the North American East Coast, a number of places are named “Hog Island.” Ever wonder why? The Spanish dropped pairs of pigs on uninhabitable islands as a future food source. Pigs were also a staple food not only for English farmers, but for the Native people who discovered the pigs roaming wild in the woods. Since most Native American cultures felt that animals did not have human owners, they did not hesitate to take advantage of this new food source. This became a sore spot between the colonists, who felt they owned the pigs, and their Indian neighbors. In Virginia, the Powhatans’ killing of pigs and cattle became a rallying point for Bacon’s Rebellion.

The Boar or pig, A New Complete, and Universal Body, or system of Natural History, 1785, From The Library at The Mariners’ Museum.

Cattle: (Old World)

In 1493, Christopher Columbus carried cattle with him on his second voyage. And although it took European cattle longer than the horse or pig to adapt to the wet, hot climate of Central America, by the 1520s there were over 8,000 of them. Cattle were used as work animals in the sugar fields and mines. They also became the favorite food of pirates. Pirates smoked the wild meat, which in French is boucan. Wonder where the name “buccaneers” came from?

Cows began having calves three times a year, and the young were larger than their parents. The new American-born cattle became lean, tough, and more suited for long drives than their European ancestors. Spain had a minor tradition of cattle driving which grew in the Americas. By 1521, cattle were being bred in Mexico and moved north to present-day Texas.

Mexico also became the major supplier of cattle to the remote grasslands of the New World. After 1540, cattle imports from Mexico to Peru spread onto the Argentine Pampas, which proved to be the most productive cattle-grazing land on earth. By 1600, some 45 ranches had been established on the Ilanos of northern South America, and by the 1680s, the first cattle ranches were operating north of the Rio Grande in what is now Texas.

Sheep: (Old World)

On his second voyage in 1493, Christopher Columbus brought sheep to Espanola and the Antilles. The first sheep brought to the Americas were probably Spanish churros. These shaggy sheep adapted well in semi-arid climates, but not in moist tropical climates—can you imagine what it must have felt like wearing all that wool? The sheep were resilient though, and had the ability to survive not only in grassy environments, but also where it was drier and had less forage than horses and cattle needed. Sheep were also able to withstand long drives to market and eat succulent plants for water in arid areas. They eventually became a staple food for the native populations. In 1525, Peru became a home for sheep where they thrived in the higher elevations. The sheep, along with indigenous llamas, created a large woolen industry in Peru and by 1571, there were 70 woolen mills. Argentina and Chile discovered the advantages of the sheep and developed sheep herding; in 1614, Santiago, Chile, counted 623,825 sheep. Moving north, 4,000 sheep were brought to the present day United States by Juan de Onate, explorer and founder of the first European settlements in the upper Rio Grande valley of New Mexico. Navajo tribes created a culture around these sheep, developing a brand new breed.

Goats: The Poor Man’s Cow (Old World)

First brought to Espanola by Christopher Columbus in 1493, goats did not thrive well in the tropical climates of the islands, but excelled when moved to the mountain regions of Puerto Rico, Venezuela, and the Chilean Islands. Upon their arrival, goats were bred in the mountainous The Boar or pig, A New Complete, and Universal Body, or system of Natural History, 1785, From The Library at The Mariners’ Museum. December 2008 ~ Mariners Weather Log 9 regions of the Antilles, and they were able to eat small animals, birds, and reptiles. They also ate a variety of plants there including flowers, lichen, mosses, branches, and leaves. In fact, goats transformed the landscape by eating ground vegetation and tree branches as far as they could reach. This killed trees, caused erosion, and resulted in the disappearance of many species of small animals. Goat herds became feral in these rocky climates.

Goat milk, meat, and hides became staples in a variety of cultures. African slaves began to own and herd goats as a supplement to their diet. They were valued for more than the food they provided; on market days, goat products could be bartered and traded.

Chickens: (Old World)

Chickens arrived in America in 1493, when Christopher Columbus brought a variety of livestock on his second voyage to the New World. Chickens were a staple on exploration ships since they were able to withstand the rigors of the voyage. African slaves also benefited from chickens, raising them to supplement their diets and selling them during market days. Europeans traditionally kept chickens close to home and fed them grains, but in the New World, many settlers gave their fowl a larger area to roam. The chickens were fed maize and ate seeds from wild plants and insects. The American chicken subsequently developed into a hardier bird than its European ancestor.

Burro or Donkey: The Workhorse of the New World (Old World)

Burros became the pack animal of the New World. Smaller than horses, they were able to go long distances with heavy loads. New World.”

Zuni tribes adopted burros as pack animals, and throughout the Americas they was used for transportation, millwork, packing, and developing mule stock. Did you know mules are American, resulting from the mating of the European male donkey and female horse? This new breed of animal was stronger and more disease resistant than either of its parents and far better suited for the tropical climate. Mule ranches began to spring up in sub-tropical climates and eventually replaced the burro as the pack animal of choice in the New World.

Rats: Old World Varmints (Old World)

Rats were stowaways, believed to have arrived in America on Christopher Columbus’ first ships, especially during the second voyage of 1493. The black rat is believed to be the first to arrive, and could carry a variety of diseases, including the bubonic plague and typhus. There is some debate about whether it was the indigenous rat population that took over the Caribbean Islands or the Old World variety. Bermuda did not have any rats until the arrival of Europeans, so what does that tell you? With no natural predators, rats practically ate the humans out of house and home in the 17th century. Not only did they eat grain and other food stores, but small animals, causing the extinction of some species. It’s interesting to think that rats were some of the most successful colonists in the New World. They adapted to their new home quickly and by the 1700s could be found from Quebec to Patagonia.

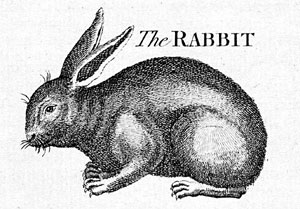

Rabbits: (Old World)

Europeans brought rabbits with them as a convenient food source. With their high fertility rate and in the absence of natural predators, there were many, many (did we mention many?) rabbits. By 1540, La Palma, California was overrun with rabbits, and every plant in sight was nibbled to the ground. Eventually, to control the population, great rabbit hunts were started and continue to this day.

Rabbit, A New Complete, and Universal Body, or system of Natural History, 1785, From The Library at The Mariners’ Museum

Honey Bees: (Old World & New World)

Honeybees are believed to be native to the New World, but historians believe Europeans also brought honeybee hives with them to the Americas. Honey was the main sweetener for the explorers and early colonists until sugar cane fields were established. Killer Bees arrived in Brazil from Africa in 1957.

Dogs: (Old World & New World)

Dogs were not man’s best friends like they are today. Dogs that were native to the Americas tended to be work animals, hauling goods on the Great Plains or helping with hunting game. Christopher Columbus brought more dogs to the New World in 1493. And Europeans brought their hunting dogs, introducing a new use for the dog as a comrade in arms. The Spanish were the first to use dogs during battle in the Americas. Their dogs were trained to attack an enemy on the battlefield or while invading a village. European dogs were fiercer and bigger than their New World cousins, and they could attack and kill a Native American warrior easily. Eventually, these battle-trained dogs ran away, living in wild packs. These feral dogs killed small game and almost wiped out some animal species. They also became a danger to humans, attacking unsuspecting natives, colonists, and slaves alike. Groups armed with guns would go out to hunt down these dangerous packs of wild dogs.

Cats: (Old World)

Cats, like dogs, were brought over in Christopher Columbus’ first voyages to the New World. They were not kept on the ships to purr in the sailors’ laps, they had an important job: control the rat populations. They were good at it, but they also saw an opportunity and followed the rats as they jumped ship, finding a new home. The islands of the Caribbean did not have any natural predators that could control the cat populations and feral cats became a problem for the Americas. Like the rat and the pig, they ate small animals, reptiles, amphibians, and birds, wiping out many species. For a while, dogs were used to help control the cat population, but they, too, became wild. Today, more than 500 years later, feral cats are still a major problem all across the Americas.

Cat, A New Complete, and Universal Body, or system of Natural History, 1785, From The Library at The Mariners’ Museum

Guinea Hens: (Old World

During the European colonization of the Americas, Africans were imported as slaves. Many Europeans felt that if the Africans were allowed to have food like that of their homeland, they might adjust better to the condition of slavery. Introducing the guinea hen. Originating in Northern Africa, the guinea hen was domesticated in Europe in the 4th century BCE Slaves were allowed to grow crops like yams and melons and raise goats, chickens, and, yes, guinea hens. Their eggs are also high in protein and very abundant. The guinea hen adapted well to the free-range atmosphere of the American plantation system and colonists quickly adopted them. And since guinea hens made noise when anything approached them, they became good “watch dogs” for frontier farmers.

Turkey: (New World)

The Aztecs had tamed the turkey by the time Spanish conquerors arrived. In 1519, Hernan Cortes introduced the turkey to Spain. It spread quickly as a delicacy on European tables, arriving in England by 1541. The Pilgrims then brought the domesticated turkey to America, only to find the wild variety in abundance. The wild turkey, an easy target for hunters, was almost wiped out in North America until conservationist groups stepped in to save it.

Llama: (New World)

Would it surprise you to know there were members of the camel family found in the Americas? The llama, alpaca, guanaco, and vicuna are all members of the camel family found in the Americas. The Incas of Peru had domesticated the llama by the time the Spanish arrived in the 1500s. They were used as pack animals and for food. Their wool was used to make fabric, and their dried dung was used as fuel for fire. Europeans thought the animal odd looking, but quickly discovered just how useful they were in carrying heavy loads through the rocky Andes Mountains. The wool produced by the llama became competition to the thriving sheep wool business. Today, the llama is still primarily raised in South America, but there is a growing number of llama herds in North America.

Gray Squirrels: (New World)

Gray squirrels, those familiar backyard entertainers, made their way from North America to England. Harmless as they may seem, they have almost completely eliminated the red squirrel population in Europe.

Vine Aphid and Grapes: (New World)

One of the earliest cultivated plants, grapes are now used primarily, and very successfully, for fermentation into wine. But it wasn’t always that way. The Spanish tried very hard to produce wine in the New World, but were disappointed by the poor results. It was not until the conquistadors reached Peru that vine cultivation was successful, and in 1551, the first Peruvian wine was made. One hundred years later, enough wine was being produced to begin exporting it to Europe. Chile also became a source for wine; in fact, in 1614, the Catholic diocese of Santiago, Chile, produced 200,000 jugs of wine.

You may be thinking, what about California? Wine production in California, now so popular, had many failures before cultivation was successful in the Sonoma region in 1857. And what about the vine itself? The Spanish used mostly European vines, but in California they experimented with the American vine, Vitis riparia. In 1860, the wine being produced was so good that they exported American grapevines to Europe. What they didn’t know was they were also exporting a vine aphid living on the plants. The American grapevine was resistant to the aphid, but it began to kill the European, North African, and Australian vines. This bug, Phylloxera, attacked the leaves, keeping the host plant from producing grapes. Over one billion liters of wine was lost. It took 40 years to find a way to stop the aphid by grafting the infected vines onto American roots that were naturally resistant to the aphid.

Chiggers: (New World)

A native of America, the chigger spread to Europe and Africa. Oviedo, a Spanish Explorer in the southwest of North America, described this insect 400 years ago, saying that it “penetrates the skin of the feet and forms a pocket as large as a chickpea between the skin and the flesh. It swells with nits, which are the eggs the insect deposits. If it is not taken out in time, the nigua grow and increase so that the men are so severely affected that they are crippled and remain lame forever.”

Disease

Small Pox: (Old World)

disease in the densely populated regions of Europe in the Middle Ages, but it was not a common killer. Plus, all survivors had a lifelong immunity to small pox because of their childhood bout with the disease. Historians believe that the small pox virus first arrived in the New World around Christmas, 1518.

It traveled quickly. One man, it was said, was to be the cause of the Mexican small pox epidemic that killed most of the Aztecs. Also, the native population’s lack of immunity to the disease caused it to run rampant throughout the Americas; one-third to one-half of the entire native population died of small pox. With so many dying of the disease, the Spanish were more easily able to conquer the natives. Small pox continued to be a major killer of native populations up into the western expansion of the United States.

Influenza: (Old World)

A sneeze. That’s all it took. When the first European explorers sneezed on the natives, flu epidemics began, just like that. The highly contagious influenza strains, which the Europeans had developed immunity to, were accidentally brought to the Americas and the natives found them deadly. Without a way to sterilize clothing or dishes, the flu continued to rage in the Americas.

“Manieres des Indians sur la Saigne & Guerison des Fieures,” NaaukeurigeVersameling der Gedenk-Waardigste Reysen Naar Oost en West-Indien, Mit Sgarders Andere Gewesten Gedaan; Zedert Het Jaar, 1492 Tot 1499, 1706, From The Library at The Mariners’ Museum.

Other Diseases: (Old World)

Early soldiers and sailors introduced bubonic plague, typhus, chicken pox, cholera, cowpox, measles, and many other diseases to the Americas. Yellow fever and malaria also traveled, originating in Africa and finding their way to Europeans and Native Americans by way of mosquitoes. The tropical rain forest of the Americas became perfect breeding grounds for the mosquitoes that transmitted sickness from infected individuals to healthy ones. These previously unknown diseases ran like wildfire in the Americas and, in fact, are still a threat to isolated native populations.

Diseases Native to America:

Historians believe that tuberculosis, dysentery, and parasitic diseases were common in the Americas. Research on early skeletal remains has also given scientists intriguing clues to early diseases and treatments. Not too long ago, in 1975, a pre-Columbian mummified child from Peru was examined, and the skeleton, as well as the preserved soft tissue, showed signs of tuberculosis with remnants of tuberculosis bacilli still in the tissue. This was proof-positive of the New World’s problems with tuberculosis before the Europeans arrived.

Back to top