Red Alert

This article first appeared in, and is reprinted with kind permission, Seatrade magazine by Neville Smith.

It had, if such a thing were possible, a touch of the ridiculous about it. The hijackers of the Vela-owned VLCC Sirius Star received their ransom by parachute, in a container dropped onto its deck from a light aircraft (see photo page 4). Subsequent reports that five of the hijackers drowned as they made for shore in a small boat brought some grim pathos to a story that had captured the imagination of the world’s media and finally brought attention to the piracy epidemic off the Horn of Africa.

But talismanic though Sirius Star is, the ship’s release for a reported $3m is a reminder of the struggle still going on in the waters of the Gulf of Aden now that the news agencies’ interest is elsewhere. It goes on in shipping’s typically mundane way, but at least with growing hope that the problem is being contained. Incidents are continuing but successful attacks are declining, in part as a result of the dedicated naval presence and also through the actions of shipowners.

Statistically, the news is not good. The International Maritime Bureau reports that 2008 saw the highest level of pirate attacks since it began reporting in 1992, largely as a result of the Somalia situation.

The key questions that remain include whether the combined EU, US and coalition forces represent anything more than temporary relief. Given the continued instability ashore, might shipowners have to accept that the Gulf of Aden will remain a high risk and costly area through which to pass? If solutions exist, can any lessons be learned from the experience of fighting piracy in the Malacca Strait?

Despite a quieter end to 2008, piracy levels increased in the first weeks of January with at least two vessels reported hijacked and 13 attacked, some more than once. The response of the naval forces has been more concerted, with French, Danish and Indian navies intervening. Some pirates have been disarmed and released but more handed over to the authorities in Puntland, who have indicated an intention to prosecute.

The increase in naval activity is a direct result of changes to the forces patrolling off Somalia. In addition to Russian, Indian, Chinese and US ships, two dedicated missions, the CTF 150, lately renamed CTF 151 and EU ATALANTA taskforces have brought additional muscle to the process of protecting shipping.

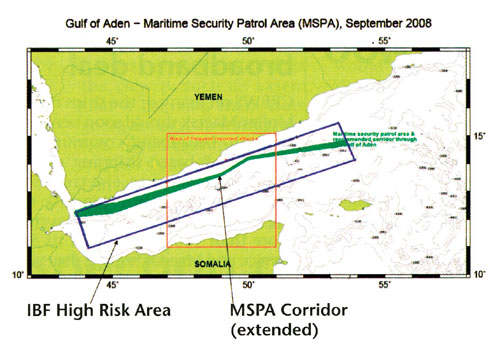

Both dedicated missions and other assets police the Maritime Security Patrol Area (see overleaf) and UK Maritime Trade Operations Transit Corridor (UTC). EU NAVFOR command has repeated its advice to merchant shipping that best protection can be afforded ships which transit this corridor, while avoiding entering Yemeni territorial waters. Under UN Security Council resolution 1846 the combined forces may enter Somali waters but the navies have also repeated that early communication with the fleet, via the Maritime Security Centre-Horn of Africa is encouraged.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the military presence in the UTC is about 10 ships at any one time but the heads of EU ATALANTA and CTF 151 have been quick to praise the increasing engagement and preparedness of shipowners in repelling attacks.

Moves are being made at diplomatic level too, with 24 countries and five organisations coming together at the United Nations in mid-January to form the Contact Group on Piracy, which will co-ordinate anti-piracy action by states and industry. The first meeting included representatives from the US, UK China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and the IMO, and established teams to organise operational and information support for counterpiracy efforts. Stronger powers on arrest, detention and prosecution were discussed and a statement noted the primacy of Somalia in rooting out piracy and the importance of building up the country’s operational capacity to fight pirates.

In the short-term, shipowners will continue to pay the price for Somalia’s internal problems. Already feeling the pinch from the collapse in rates and the prospect of reduced demand, owners have swallowed a tenfold rise in insurance costs for transiting the Gulf of Aden, where crews now receive danger money equivalent to double pay.

The London insurance market’s Joint War Committee responded to the surge in attacks late last year by increasing the sea area where War Risk premiums can be charged. The JWC has extended the area off the eastern Somali coast to 250 miles, south of latitude 10deg N and created a new area up to 600 miles into the Indian Ocean between latitude 15deg north and 10deg south, reflecting the wider scope of pirate attacks.

Charterers are also starting to turn the screws on owners, with the London P&I Club issuing a circular warning owners to look out for ‘Gulf of Aden clauses’ in contracts that might commit them to using the route while offloading a charterer’s liability if a vessel is seized. Even the option of transit around the Cape of Good Hope, touted in the last few months as a safer, albeit more expensive alternative, might actually be removed from some charter parties.

The London Club warned that charterers will increasingly be able to extract more onerous terms in the depressed market and restrict the option of re-routeing if the master requests it. The club points out that deviation from a customary route should only be made ‘in-co-operation with charterers and cargo owners.’

Another P&I provider, Skuld, says that even without specific clauses, owners must judge whether conditions in the area have changed since the contract was made, but notes that orders to proceed via the Gulf of Aden would be legitimate and binding.

While shipowners might be able to take some comfort from improved security arrangements, the deployment of increased naval forces implies that the countries involved see no quick end to the problem.

The parallels with the spate of piracy in the Malacca Strait, which accounted for 40% of incidents world-wide in 2004, are clear but not necessarily encouraging. In that case, Malaysia and Singapore were able to field paramilitary resources to mount patrols and with assistance from the Indian navy bring the situation quickly under control. They also had support from the Federation of Asean Shipowners’ Associations and Japan – utterly dependent on the Middle East crude transported through the strait – in pressing diplomatic buttons and providing funds by way of encouragement.

The countries surrounding Somalia lack the support of a similar vested-interest broker. Also, Somalia’s position at the crossroads of global geopolitics makes it far less likely that western nations will be able to achieve a settlement without the support of the African Union or other local body. The UN has accepted the need in principle for a peacekeeping force in the country but delayed a decision on participation until June.

Faina crew and Somali pirates following the ship’s capture in 2008

Parachuted ransom for the VLCC Sirius Star

In recent years, the US has intervened directly, using Ethiopia as a proxy to unseat the Islamic Courts Union and install the Transitional Federal Government. Given the failure of the TFG to bring stability and peace to the country, it seems unlikely that a solely US-sponsored solution will gain much support.

The Malacca situation also served to point up the conflation of piracy and terrorism in the mind of western security interests and more particularly, the terrorism risks that flow from lawlessness. There is little evidence so far of a direct link between Somali piracy and terrorism but there are reports of ransom money being routed to the Islamist insurgent group Al- Shabaab. It is no great leap to imagine that pirate groups could in future be co-opted into a terrorist network which plans suicide attacks on coalition forces or merchant shipping.

It has been said repeatedly that the solution to the Somali piracy problem lies ashore rather than at sea but this is only partly true. Certainly, so long as it remains a failed state, Somalia will be a magnet for illegal activity, particularly since the shipping industry lacks an alternative to paying ransoms. But if the maritime coalition is not an end in itself, then the willingness to deploy naval assets demonstrates that other measures could be considered.

A recent briefing paper by thinktank Chatham House suggested that even with the survival of the TFG, the international community might do better by creating an internationallysanctioned and administered Somali coast guard, run by the UN or African Union, part-funded by collection of fishing dues and import duties.

This would be cheaper than a full naval solution, safer than arming crews or deploying armed guards on merchant ships and could allow the international community to maintain security while protecting UN World Food Programme aid shipments.

After all, an end to hunger in Somalia would not be the end of the story, but it could perhaps be the beginning of it.

Back to top