Familiarization Float: M.V. North Star

Jeff Lorens, Program Manager, Marine and Coordination Services,National Weather Service, Western Region Headquarters

I was invited aboard the M.V. North Star, owned and operated by Totem Ocean Trailer Express (TOTE), Inc., for a familiarization trip (“fam float”) March 24–31, 2004. The trip would take me from Tacoma, Washington to Anchorage, Alaska, and back again. My main goals were to see first-hand how weather affects the ship’s operations, and to better understand how weather observations are taken at sea and transmitted to the National Weather Service (NWS).

|

Figure 1. M.V. North Star at Tacoma, Washington. |

The North Star is a large “roll-on/roll-off” cargo vessel (Figure 1)—839 feet in length with a beam width of 118 feet. She is one of two “Orca” class vessels built by National Steel and Shipbuilding Company in San Diego, California. Her sister ship is the M.V. Midnight Sun. Both ships are relatively new. The Midnight Sun was christened in August, 2002; the North Star followed in June of 2003. Each ship can carry up to 600 full-size truck trailers and 200 cars. She can also carry other types of large wheeled vehicles, such as buses or tractors. There are 6 cargo decks forward (5 for trailers and 1 for cars) and 5 decks aft (3 trailer decks and 2 for cars.) Loading/unloading is accomplished by driving on and off over three large, moveable ramps connecting the ship to the dock, and moving up and down within the ship using a series of internal ramps between decks. The “roll-on/off” system allows for rapid loading and unloading—the entire process typically takes no more than about nine hours.

Wednesday, March 24th

|

Figure 2. M.V. North Star loading operations prior to getting underway. |

I boarded the North Star early Wednesday afternoon, March 24th. Unloading of the ship’s cargo began later in the afternoon, around 5 pm. The loading operations started later, around 9 pm, even as the unloading process continued. For a new observer, such as myself, the loading/unloading process appeared chaotic at times but skillfully orchestrated and accomplished. Within a few hours of tying up at TOTE’s Tacoma facility, trucks began moving onto the ship and pulling trailers off. Maneuvering space for these trucks was extremely tight, especially early in the process. The trailers were parked side-by-side and end-to-end on every cargo deck. In many areas, there was only a foot or less between parked trailers (Figure 2.)

As unloading continued, the available space increased, but the trucks still had to make seemingly impossible turns on deck and in going up and down the ship’s internal ramps. There were often three or four trucks simultaneously moving on deck, sometimes moving in opposite directions within inches of one another. On this day, a steady rain made for very slick upper decks. During the unloading process, some trucks occasionally needed a little push (from another truck) in order to get into just the right position to latch with its trailer, or to get the trailer moving once latched.

For loading, trailers were pulled quickly aboard, parked and released, and then the drivers went back for another. Separate crews went from one trailer to the next, chaining each to the deck to prevent movement while at sea. Interspersed with the trucks moving on and off the ship, cars also moved aboard and were secured on the lowest cargo decks. Needless to say, the cargo decks during loading and unloading are a highly dangerous place for an untrained observer. I wisely chose to watch the entire process from above.

Thursday, March 25th

|

Figure 3. M.V. North Star heading west through the Strait of San Juan de Fuca. |

The ship was due to sail about 1:30 am Thursday morning, but our departure was delayed a few hours. At about 6:30 am, the pilot came aboard and we got underway. Our trip north from Tacoma through Puget Sound was calm and uneventful. As we turned west into the Strait of San Juan de Fuca (around noon), the winds strengthened and we also started to pick up a slight swell coming in from the Pacific. We slowed near Port Angeles, Washington to disembark the pilot, then continued westward to sea. As we neared the western entrance to the Strait of San Juan de Fuca, the swell continued to build to around 20 feet, and we occasionally took some spray over the bow. Exiting the straight into the Pacific Ocean, we turned northwest and paralleled the coast of Vancouver Island through the night, occasionally passing through rain showers and sleet. The ship’s roll increased (typically 10–15 degrees), but the strongest winds and largest seas remained south of us, in association with a strong low off the coast of Washington and Oregon. As the North Star continued northwest, winds and seas steadily abated, decreasing the ship’s pitching and rolling, and making for a very restful first night’s sleep.

Friday, March 26th

|

Figure 4. Bridge on the M.V. North Star |

I awoke the next morning to find us west of the Queen Charlotte Islands, off the coast of British Columbia. It was still mostly cloudy, but there were breaks in the clouds allowing the morning sun to shine through. Visibility was very good, and I could clearly see the mountains about 30 miles to the east. By now, the swell had subsided to around 10 feet or less, mainly from the south. As we moved into an area of weak high pressure, winds fell to about 5–10 knots, and were even near calm for a few hours. Temperatures hovered in the mid 40s—unusually calm and pleasant conditions for late March in the north Pacific. We continued northwest, moving further away from the coast through the day.

Saturday, March 27th

|

Figure 6. Rough seas as North Star heads north across the Pacific toward Alaska. |

The next morning, we were heading west-northwest across the northern Gulf of Alaska toward Cook Inlet, slowing to about 18 knots to conserve fuel. The weather worsened overnight and seas turned rougher as southwest winds increased to 25–30 knots. Temperatures had dropped to the mid 30s. Early in the morning, the visibility dropped to near zero at times as we passed through scattered snow showers. The M.V. North Star’s Captain (Jack Hearn) had earlier selected a more northerly route (slightly less direct) across the Gulf of Alaska toward Kennedy Entrance (passage between the Barren Islands and the western tip of the Kenai Peninsula), which we would pass through heading toward Cook Inlet. His experience indicated that this type of routing (mainly during winter) typically has somewhat more favorable sea conditions. The choice of the precise route on any particular trip depends on several factors, including fuel consumption, schedule, and of course, crew safety.

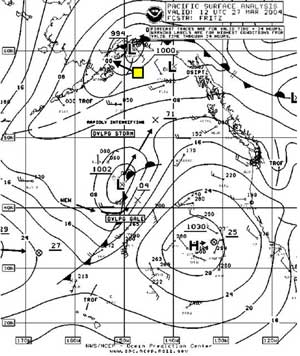

The forecast indicated that weather conditions would continue to worsen over the next 24–36 hours, with a low to our south moving quickly north and strengthening to storm force as it neared the south coast of Alaska (Figure 7.) By that time, however, we would be in Anchorage, allowing the worst of the storm to pass by before departing for the return trip Sunday night.

|

|

During the afternoon, I spent time with the Second Mate, Karl Carr as he made a weather observation. These observations are critical for preparing surface analyses and as input data for initializing numerical weather models. He carefully observed the wave conditions, and from that, he then estimated the surface wind (using the well-known Beaufort Scale.) He also compared this with the measured wind from the ship’s anemometer (taking into account the ship’s motion), but since it is located on top of the bridge, more than 130 feet above the water, it can easily vary from the true surface wind. He also observed the temperature (dry and wet bulb), pressure, pressure tendency, sky condition, and present weather. All this information was entered into the AMVERSEAS program on a PC at the weather table in the rear corner of the bridge (Figure 5.) The AMVERSEAS program automatically encoded all the information, which was then saved to a file on a floppy disk. He then took the disk over to the ship’s communications console and transmitted it via satellite into the NWS Gateway.

By late afternoon, our winds had slackened considerably. Seas were much smoother for the rest of the day, but snow showers persisted. We passed through Kennedy Entrance about 7:30 that evening and continued up Cook Inlet overnight.

|

|

Sunday, March 28th

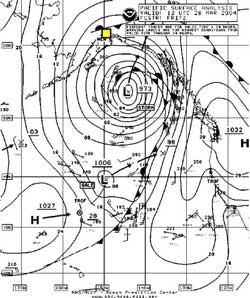

We tied up at TOTE’s Anchorage facility about 6:30 Sunday morning. The ramps were quickly raised into place and the unloading/loading process began again. The weather was cloudy and cold, with a moderate north wind and temperatures hovering around 20 degrees (see Figure 10 for surface analysis.) Despite the cold, I took the opportunity to get off the ship and venture into Anchorage for a few hours.

|

|

Upon returning to the ship later in the afternoon, loading was nearly complete. There were fewer trailers and no cars aboard this time. Most of the trailers were empty, meaning the ship would be lighter for the return trip—somewhat more prone to pitching and rolling. We again were underway about 7 pm that evening, and the trip back down Cook Inlet was a smooth one for the most part.

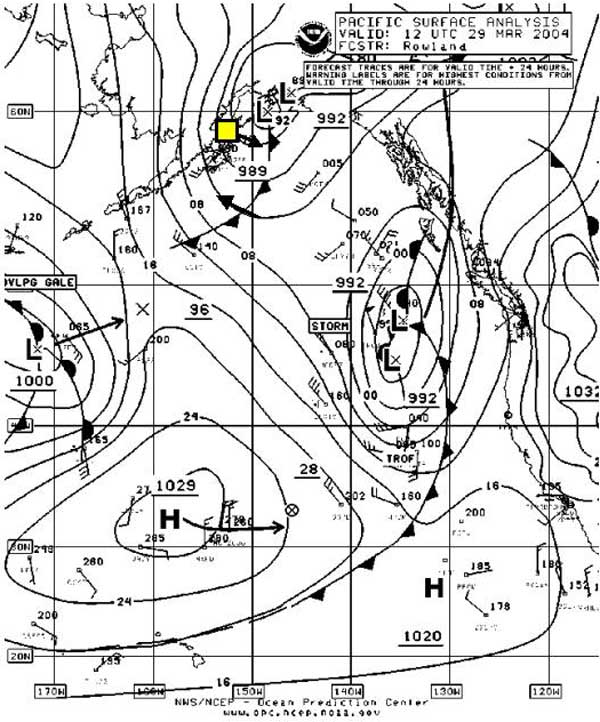

Monday, March 29th

We crossed back into the Gulf of Alaska about 4 am on Monday and turned east-southeast. By being in port the previous day, we avoided some strong winds and rough seas associated with a deep surface low, which had moved north-northeast across the Gulf and moved inland to the east of us. During the morning, our winds were from the west to northwest, but as we continued on our track, the wind shifted to the southwest and increased to aound 30 knots, while seas increased to around 12 feet. The deep surface low in the northeastern Gulf of Alaska had quickly moved inland, but at the same time, another low dropped south and moved off the southern coast (Figure 13.) A strong surface pressure gradient behind the low gave us some strong following winds as we moved south out of Cook Inlet and into the Gulf. As expected, the ship’s motion increased due to higher waves, but it was not as bad as it would have been had we been going into the wind and waves. During the afternoon, however, the wind and seas decreased as the low moved northeast and the pressure gradient eased.

Later that day, the North Star’s Chief Engineer Harry Poole gave me a tour of the engine room and other engineering spaces on the North Star. I was impressed with the complex interaction of systems—propulsion, electrical, and “plumbing” systems, and the technology used to monitor and control it all.

Tuesday, March 30th

By Tuesday morning, we were once again off the Queen Charlotte Islands, heading southeast parallel to the British Columbia coast. Our weather was good, except for occasional showers. A cold front had earlier pushed inland and we were now moving into a ridge of high pressure behind the front. The forecast for our last full day at sea also looked good. Another frontal system to the west was moving toward the Pacific Northwest, but it was expected that it would stay mostly north of us as we entered the Strait of San Juan de Fuca the following morning.

Wednesday, March 31st

|

Figure 14. Rough seas as M.V. North Star heads back toward Tacoma across northern Gulf of Alaska. |

We entered the Strait of San Juan de Fuca just before sunrise. Although mostly cloudy (from the approaching frontal system), winds were light and the waters were nearly calm at times. We again picked up the pilot near Port Angeles, then continued into Puget Sound and south to Tacoma. We tied up at the TOTE dock at about 1 pm. Although my journey was done, the crew quickly made preparations to turn around and repeat the trip once again.

Although the weather on this particular trip certainly could have been a lot rougher, I nevertheless gained a better understanding of the critical role weather plays in operations and route planning for large cargo ships, such as the M.V. North Star. Captain Hearn indicated that the weather information provided by NWS plays a major part in his decision-making, both at sea, and in port getting ready for sea. Using weather data provided by NWS, the ship can often be routed to avoid the worst of the weather conditions. Although large course deviations are usually not possible, even slight course and speed adjustments can result in considerable fuel savings and enhanced crew safety. I truly hope to be able to have the chance to do this again in the future, but maybe next time my weather won’t be as smooth!

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the officers and crew of the M.V. North Star for making my trip such an enjoyable one. In particular, I’d like to thank Captain Jack Hearn for welcoming me aboard and taking the time to tell me about the ship’s operations, and how he dealt with the weather and seas. I also wish to thank Teresa Velasco, Terminal Analyst with TOTE, Inc., who arranged this trip for me and welcomed me so kindly. Finally, thanks also go to Pat Brandow, NWS Port Meteorological Officer in Seattle, WA, who initially facilitated the trip, and then made several follow-ups with TOTE, Inc. throughout the process.

Page last modified: